Blogs like this one talk a lot about the sort of dreams we have for our lives—the goals, aspirations, and ambitions people think of when someone says, “Livin’ the dream.”

Blogs like this one talk a lot about the sort of dreams we have for our lives—the goals, aspirations, and ambitions people think of when someone says, “Livin’ the dream.”

But the reference in this post is the other kind of dreams, those visions that appear to us while we are sleeping and that we tend to dismiss as “what a crazy dream that was!” We blame the food we ate the night before or the terrible thing we saw on television. The last thing that occurs to us is that the dream was actually a spiritual experience.

The worst thing about these dreams is how ephemeral they are. If you don’t write them down or take some other measure to purposely capture the dream, it is gone from you as completely as though it never happened.

And that would be a terrible shame because there is always a chance that the dream has an important message for you. You can call the source of the message your own subconscious or the universe or God. Doesn’t matter. It’s a source that has a clearer viewpoint on your circumstances than you do.

Sometimes it pays to ask for a dream that will hold a guiding message for you. Just the asking puts you in a frame of mind for receiving. It indicates willingness to take direction, to be open, to listen. Then when the dream comes, don’t edit it. Just be sure to put down on paper every single aspect of it you can recall, especially the ones that you cannot immediately interpret. And this writing down must be done as soon as possible after waking because, like snowfall on a sunny winter’s day, the edges will melt away fast.

I could give you examples from my own life, but much more effective for you are examples from your own.

Ask for the guiding dream, be open to whatever comes to you no matter how little sense it seems to make at first, write down every detail, ask God for the interpretation, act on what you learn.

Now that’s livin’ the dream.

Every day I send at least one text to a friend of mine in another state. Today when I typed in “Good Morning,” my autocorrect feature immediately double-checked and offered me the alternative of “Mourning.”

Every day I send at least one text to a friend of mine in another state. Today when I typed in “Good Morning,” my autocorrect feature immediately double-checked and offered me the alternative of “Mourning.” Words and God have always had my heart.

Words and God have always had my heart. Everyday Spirituality is about experiencing the divine in the mundane and seeing lessons where problems are apparent.

Everyday Spirituality is about experiencing the divine in the mundane and seeing lessons where problems are apparent. The sun is out shining brightly; flowering cherry trees are in bloom; buds are already abundant with new life. This time of self-isolation, instituted in an effort to slow or stop the spread of the coronavirus, is also a time of stopping to notice what is around us.

The sun is out shining brightly; flowering cherry trees are in bloom; buds are already abundant with new life. This time of self-isolation, instituted in an effort to slow or stop the spread of the coronavirus, is also a time of stopping to notice what is around us. James Broughton wrote a wonderful, short poem, which I first noticed seven years ago and some small part of my mind has been thinking about since. It appears at the end of this post.

James Broughton wrote a wonderful, short poem, which I first noticed seven years ago and some small part of my mind has been thinking about since. It appears at the end of this post. I know this picture doesn’t look like much to you. But actually something remarkable has happened, and this photo is the proof.

I know this picture doesn’t look like much to you. But actually something remarkable has happened, and this photo is the proof. Today is an unexpected day off in the middle of a week-long fence-repair project. My contractor has pruned all the plants in the flower beds on the sides of the fence and covered them with painters plastic. She has replaced a rotten board or two and used a strong cleaning product along with a brush to remove algae. Through the process, the boards got a good soaking. She asked me to check the bottoms of the boards this morning to make sure they were dry enough for paint.

Today is an unexpected day off in the middle of a week-long fence-repair project. My contractor has pruned all the plants in the flower beds on the sides of the fence and covered them with painters plastic. She has replaced a rotten board or two and used a strong cleaning product along with a brush to remove algae. Through the process, the boards got a good soaking. She asked me to check the bottoms of the boards this morning to make sure they were dry enough for paint. You could almost say that faith is a gift that keeps on giving. That is, no matter how many times I visit the issue of faith, there comes another time when the subject deserves another look. It’s a very big subject.

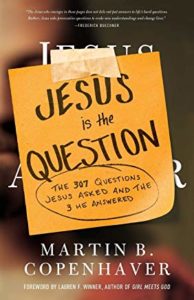

You could almost say that faith is a gift that keeps on giving. That is, no matter how many times I visit the issue of faith, there comes another time when the subject deserves another look. It’s a very big subject. What prompts my latest reconsideration of this vast subject of faith is the book my Sunday study group has been reading: Jesus Is the Question: The 307 Questions Jesus Asked and the 3 He Answered, by Martin B. Copenhaver. A few weeks ago, the group took up Chapter 4: “Questions about Faith and Doubt.” In those pages was a quote by William Sloane Coffin: “Faith isn’t believing without proof—it’s trusting without reservation.” [Coffin was a former Yale University chaplain who was instrumental in creating the Peace Corps.]

What prompts my latest reconsideration of this vast subject of faith is the book my Sunday study group has been reading: Jesus Is the Question: The 307 Questions Jesus Asked and the 3 He Answered, by Martin B. Copenhaver. A few weeks ago, the group took up Chapter 4: “Questions about Faith and Doubt.” In those pages was a quote by William Sloane Coffin: “Faith isn’t believing without proof—it’s trusting without reservation.” [Coffin was a former Yale University chaplain who was instrumental in creating the Peace Corps.] I was saddened to see the announcement yesterday of the passing of Mary Oliver, longtime favorite poet of mine and of many others in my circles. What an extraordinary woman and writer! I first fell in love with her over her poem “The Summer Day,” which asks big questions like “Who made the world?” and states big thoughts like “I don’t know exactly what a prayer is,” then devotes the heart of the poem to a grasshopper she has happened to meet. That’s the poem that ends with her famous question: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

I was saddened to see the announcement yesterday of the passing of Mary Oliver, longtime favorite poet of mine and of many others in my circles. What an extraordinary woman and writer! I first fell in love with her over her poem “The Summer Day,” which asks big questions like “Who made the world?” and states big thoughts like “I don’t know exactly what a prayer is,” then devotes the heart of the poem to a grasshopper she has happened to meet. That’s the poem that ends with her famous question: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”